So what exactly is Dungeons & Dragons?

Broadly speaking, it’s a tabletop role-playing game. In a practical sense, however, it is… Several not too thick books. To be precise, the complete set of the latest, fifth edition of D&D consists of three volumes. “Player’s Book” describes the rules of the game, “Encyclopedia of Monsters” gives information about the monsters to be fought, and “Master’s Guide” contains useful cheat sheets for the host.

That’s it? What about the figures, the three-dimensional fields, the twenty-sided dice….

This is a fairly popular misconception among newcomers. When you talk about D&D in colors, people often imagine something absolutely monstrous and incredibly expensive. But in reality, everything is much simpler: the only thing you really can’t do without is the Player’s Book. It is in it that you can find everything you need, from the rules of creating and upgrading a character to the combat system. Other little things, like the same figures, are optional – it all depends on how much you and your group want to get involved. Even unusually shaped cubes – the key element of the system – can be replaced with a smartphone app if you want.

The master screen is the second most recognizable element of the game after the dice. And no, it is not just for beauty: the master keeps all the most important information there. But if you want, you can make an even cooler screen out of a notebook – the Internet helps when you need to quickly check some nuances

Wait, how does the game play out?

From the outside, a D&D game looks like a long conversation, with the conversation occasionally interrupted by dice rolls. Players get comfortable, having prepared their inventory: character slips, where their characteristics and abilities are written down, someone can take his own set of dice or a notebook to make notes. At the head of the table sits the host, who is more often called “master” or simply “DM” – from the English term dungeon master. He plays the roles of NPCs in dialogs, describes the surrounding world, controls monsters in battle – in short, he makes sure that the game goes as it should. He also gives the players the plot twist, based on the text of the adventure. The DM knows in advance what key events are going to happen, what locations the players can explore, and what kind of monsters inhabit them. In short, it’s the same as Dragon Age or any other video game. The only difference with computer RPGs is that in “digital” the computer is responsible for this, while here – a live person.

In terms of mechanics, the older Neverwinter Nights came closest to the tabletop original

The entire gameplay is essentially a dialog between the wizard and the players. The DM describes a particular situation in detail, and the players respond by saying what their characters are doing. For example, he tells how the group is approaching the entrance to a large cave where a gang of goblins is lairing. And one of the players immediately replies that his character, a robber elf, will go ahead – he can see in the dark better than the other players and will quietly scout the way.

When players start something risky, the dice – the same twenty-sided die, d20 – comes into play. Let’s say there are traps in the tunnel the bandit is sneaking through, so the wizard asks for a Perception check to see if the character has noticed the trap. And if he’s already trapped and the ceiling above his head is about to collapse, a Dexterity check to see if he can dodge at the last moment.

Any experienced roleplayer will tell you that there are not a lot of cubes. And the search for unusually beautiful or stylized sets is a separate story

The wizard then interprets the result of the roll and tells you what happens next. If the player fails the check, his character may take damage from a trap, or the goblins gathered around a fire somewhere in the cave will hear a noise – now they can’t be taken by surprise. And if successful, the bandit will have a chance to disarm the stretch. If you don’t make a lot of noise, you can ambush the monsters – or make them fall into their own trap. It all depends on your cunning.

So in D&D you have to play with words?

To put it quite crudely, yes. That’s why tabletop RPGs are sometimes called “word games” or “word games”, although that’s not quite right.

In fact, D&D has much more in common with theater than with computer RPGs. Each game is a small production in which the entire table participates. And players are both actors and spectators: the more they believe that everything is real, the more interesting it is to play. It sounds complicated, but in fact it’s quite easy to immerse yourself in the process. Just turn on the soundtrack of your favorite fantasy movie or game in the background and make a little effort. For example, address other players by the names of their characters. The imaginary world turns into a real one, and in good company you won’t even notice how quickly you’ll start to take the game seriously.

Music helps a lot to create an atmosphere at the table, and enthusiasts even create a separate app for this purpose. For example, Syrinscape, where you can change ambient and sound effects in real time

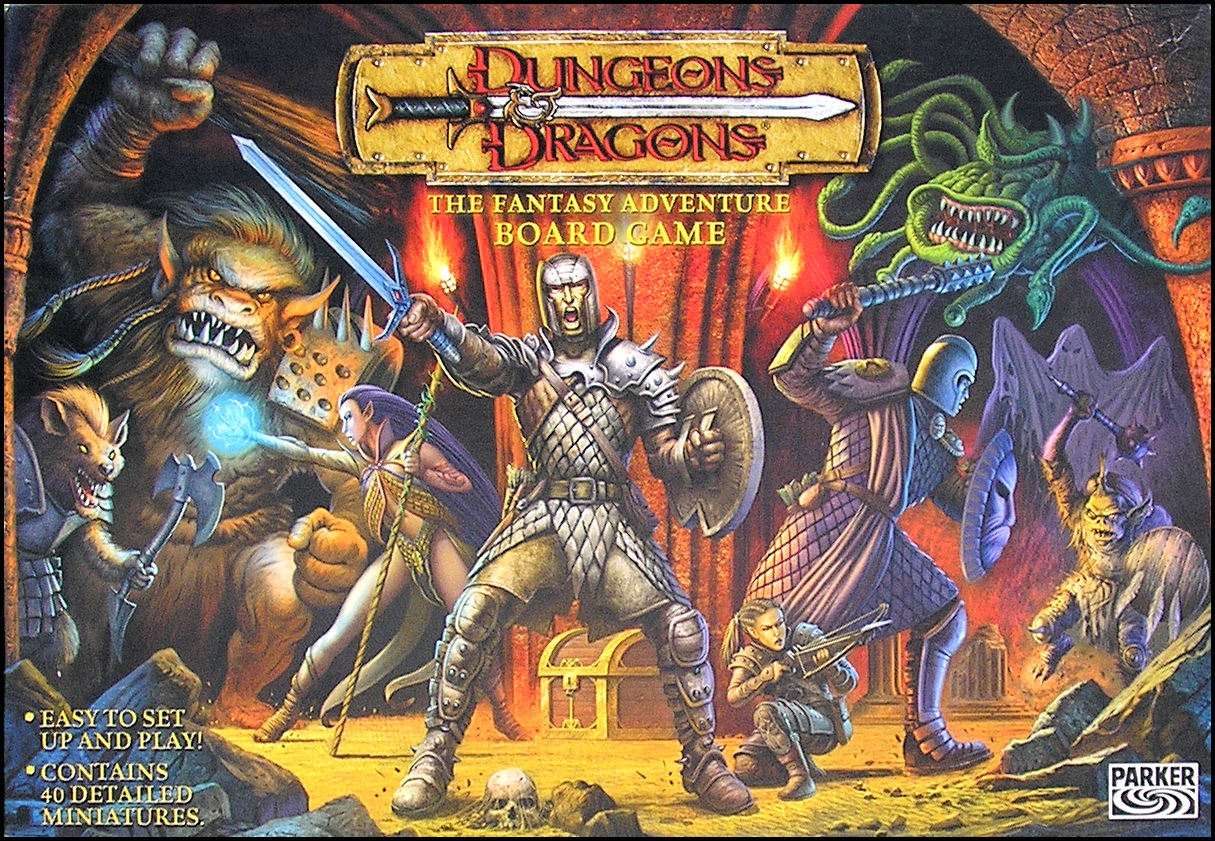

That’s why props like character figures aren’t always necessary. These nice little things only help to get into the mood and visualize the game. Many masters prefer to play dialogs and other social moments without scenery, because it saves a lot of time and money. But battles, where it is important to clearly visualize the balance of power, is another matter. Battles in D&D are like in any other turn-based strategy: players, like monsters, have many different abilities, and here you need to take into account distance, position and landscape. For this purpose, some groups bargain together to buy sets of miniatures, others use scrawled paper and Lego men, and others use a sketchbook and colored pencils. You name it.

It all sounds kind of… painful. Why bother when you can always replay Planescape: Torment or the second Baldur’s Gate for the hundredth time?

Yes, D&D has a few pitfalls, and it’s silly to deny it. First of all, it is physically impossible to play it alone: you need a master at least at all times. And preferably at least two more players. Just to keep the group dynamic going; the more characters, the more different skills, opinions, and personalities. Unfortunately for all introverts, this is where you have to come out of your shell.

Secondly, D&D takes up a lot of your free time. It’s not the kind of hobby you can do in between. One game (game session) on average takes from three to five hours – you need to give the whole day to it. And not just for you, but for everyone. Both the master and the players. And to do this, everyone’s schedules have to coincide: some have work, some have families, children, and other concerns. D&D gatherings should be planned well in advance, and there is no guarantee that your group will meet regularly. Once in two weeks, or even once a month is already a great achievement. Therefore, going through even one campaign can easily drag on for a year.

Thirdly, the gameplay is strongly tied to improvisation, and some players have a hard time getting used to it. In the same dialogs you don’t have pre-prepared lines in front of you – you have to come up with them here and now. It’s even harder for a wizard in this sense: no matter how thorough his plan is, players will always find a way to break it – sometimes you have to come up with whole plot branches on the fly. And when there are five people at the table, it’s a shame to think about every decision for 15 minutes. You don’t want to slow everyone else down and break the pace of the game by treading in one place.

Wait, but I don’t know how to drive!

And no one demands that you play flawlessly the first night. The only way to become good at it is to practice. Yes, from the outside, the position of DM looks difficult and responsible. That’s partly true: running any roleplaying game is not easy. But, again, the most important thing here is to take the first step. At first it will be difficult, but with each next game you will get more and more pleasure from the process. The main thing is to make sure that your company is having fun.

It is better for a beginner to drive a script written specifically for beginners as a test pen. Don’t worry, it won’t be boring or too easy – just in such books authors usually leave useful hints for the master. In this regard, The Lost Mines of Fandelver would be a good choice. A company of three or four people can buy a box as a bargain, and there is everything you need: a book of adventure, a shortened version of the rules, ready-made characters and a set of dice.

Perhaps the only advice that can be given to the future master is: don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Your first game will be a mess of forgotten rules and ridiculous situations, but that’s perfectly normal. Try to keep a separate diary where you will write down the moments that are the hardest for you. Maybe you don’t know how to play out tense dialogs with NPCs or how to lead monsters in battle. And then, after the game, ask the players how it was: what you liked, what caused questions.

Tabletop roleplaying games are a hobby available to anyone and everyone, not just stereotypical geeks. In the case of D&D, this is doubly true: over the course of five editions, the authors have optimized the rules quite well, making them really simple and easy to understand. So there’s no insurmountable entry threshold – you just have to try it out. Who knows, maybe you will be drawn in?

Newbies – please ask questions in the comments! Old timers – share your best tales and stories from roleplaying. And also show me what set of dice you’re playing with, just out of curiosity.